(This isn’t a particularly cheerful or hopeful or actionable post. It is a rumination on society, and one of its present negative trajectories.)

We’ve had a reasonable debate over the right to be forgotten. The next one will be about the right to lie. Not the right to lie in court or as part of some fraud, but the right to everyday lies and white lies. Digital surveillance deprives [us] of this important part of life.

For whatever reason, I might be ashamed or shy about my age/looks/past/job/health/sexual preferences/race/ethnicity/beliefs/political views/abilities/education/family history etc. It’s valid to lie about such in everyday life. Tracking and ML should not interfere with that right.

— John Wilander, 2019-12-24

We often treat records, such as government records, as authoritative or definitive—reflecting, even to the point of creating, reality or truth. Want to know something? No need to ask the person(s) involved; just look up the record.

This practice and the mindset underneath it is commonplace for a wide range of records, including anodyne ones such as birth certificates and loan records.

Now, as anyone who’s had to correct a birth certificate or clean up a fraud-riddled credit report can attest, treating a record as definitively equal to truth can present some pretty tall barriers to fixing a discrepancy between the two. It involves asserting that there is a truth not created/confirmed by the record, demonstrating that the record is wrong, and convincing the authority who maintains that record to revise it to match reality.

Surveillance isn’t just the act of watching someone, or everyone. Indeed, in the modern era, mass surveillance doesn’t involve any individual person or persons watching anyone at all—it’s the bulk collection of phone call records, voter registrations, addresses from credit card purchases, all this data that is created whenever we interact with any kind of system. Hoover it up, save it somewhere—and you have a surveillance system. A system that creates records of what it observes.

As with classical surveillance, there is a problem here of “but what if they get it wrong?”: Records erroneously merged, data entry errors, people named “Null” who break poorly-implemented checks and comparisons. In modern mass surveillance, rather than there being a human surveillant misinterpreting your intent or mischaracterizing your actions, it is the bare facts of your life and your actions that get misrecorded. Less “surveillant thinks you’re having an affair” and more “surveillant thinks you have more children than you have” or “surveillant got your birthdate wrong”.

But the problem is not merely the accuracy of the record. It is the authoritativeness of the record. It is treating the record as an infallible determinant of truth, rather than a fallible artifact of an observation.

When we try to automatically verify someone’s identity using whatever scraps of information they’ve given us, or to let them board a plane with their face, we treat the data we have on someone as being necessarily, implicitly the same as their actual truth. We assume/trust/bet that the data we have matches the truth; that they are the same as each other, and therefore the record can tell us the truth.

When we make this bold leap into the concrete wall of bad assumptions, we create the sort of dystopia in which you can’t sign up for Hold Mail because “identity verification” just mysteriously fails. We create systems that reject objective reality and substitute their own.

We create systems that seize authorship over reality, and over our own personal truths.

That is an even greater crime of surveillance, even more than knowing too much about you/everyone, or than the risk of there being inaccuracies in the record (both of which are also severe problems).

When Wilander talks, in the tweets I quoted, about the freedom to lie about yourself, Wilander is talking about authorship of your reality. Authority over your reality.

That is: self-determination.

The freedom to lie about yourself is the freedom to tell the truth about yourself. It is the same freedom, the freedom to tell your story as you see fit, and as much as you see fit, and as accurately as you see fit. It is your exercise of your power to determine yourself, and present yourself, and determine how (and whether) to present yourself.

It is your ownership of your truth.

A system that creates records, definitive records, that other subsystems and other systems treat as the truth, and that those other systems query directly without asking us, seizes ownership over our truths away from us.

That’s dangerous enough without introducing malice into such a system. We see that now, when the system gets it wrong, when the record is inaccurate, when we have to spend our precious time and energy trying to find a real, live human being like us who (a) will believe the system got it wrong, (b) has the power to fix the record, and (c) will do so.

But when we think of surveillance, when we warn of surveillance, we are already thinking about malice—the state (or corporations, or both) acting against us.

No wonder that some of us are scared of a mass-surveillance society that has the power to write our reality without us, and confirm that (maybe-parallel) reality behind our backs, and maybe turn that reality into consequences for us ranging from inconvenient (can’t sign up for Hold Mail) to hostile (false arrest). It’s bad enough when it’s trying to help us but not always succeeding; it would be a true dystopia if (or when) it is turned truly against us.

The only record that cannot leak—or in any other way be used against you—is one that is not kept, is not recorded. But this fact becomes irrelevant in the face of malice; a system that chooses to write its records regardless of your reality, or to override your reality with the contents of its records, does not care about recording truth; it has assumed the role of defining truth, and your own truth outside of that system ceases to matter.

To guard against that is to resist surveillance in all forms, malicious and not.

Back in the present, our system of mass-surveillance/data-brokerage/(whatever facet you want to look at) is one that promises convenience. It promises to enable its users, its querents, to learn (or verify) information about a subject without their involvement (which implies without their consent). It promises to enable the construction of other systems, automated themselves, to fulfill the function of querent, to ask the questions about us that the record-keeping system promises to be able to answer.

It promises to obsolete us.

You are no more than a record to be verified and/or updated and expanded. You are not a customer, who has wants and needs and a real life that the record may or may not match; you are not an employee interacting with that customer; you are not a manager responsible for any of this. You are a card in a Rolodex and you do not hold the Sharpie.

The automation of so much of this—of identity verification, credit checks, checking out at the grocery, checking in at the airport—is, I think, part and parcel with the rise of mass surveillance. The more data we assemble on everyone, the more we can automate. And the automated systems feed data back, and contribute more.

I think the opposite of mass surveillance is also the opposite of automation. It is a focus on people, real people in the really-real world, as human beings with lives who are not the same as, nor defined by, a record. It is the awareness that the map is not the territory and the record is not the person. It is the recognition that we cannot automate our society away, because our society is us; it is made of us, by us, for us, and giving all of it over to automated systems means leaving none of it for ourselves.

That said… I have no idea how we’re gonna get there.

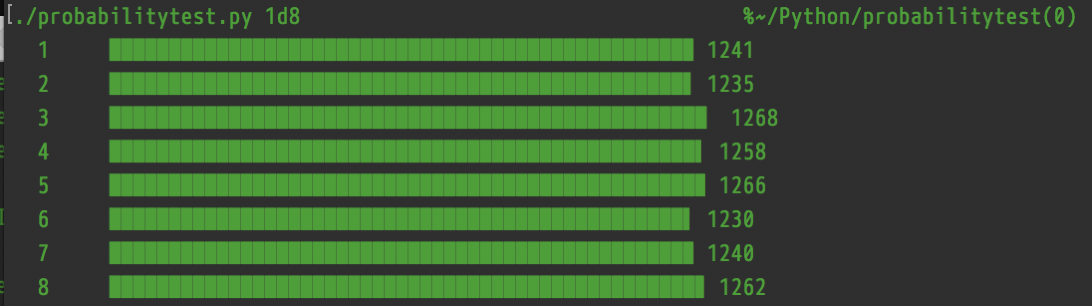

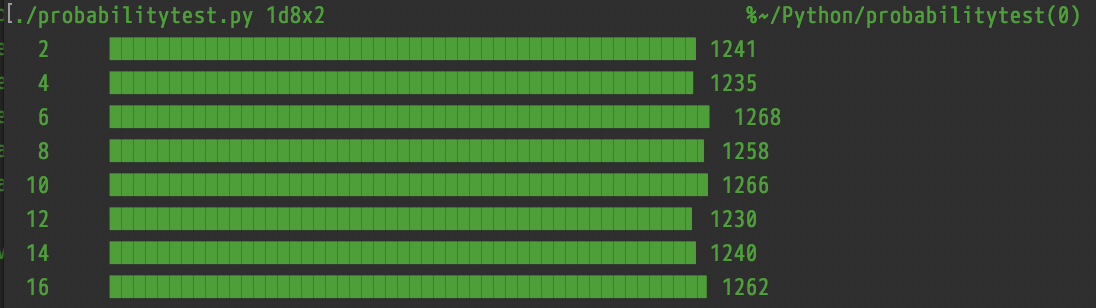

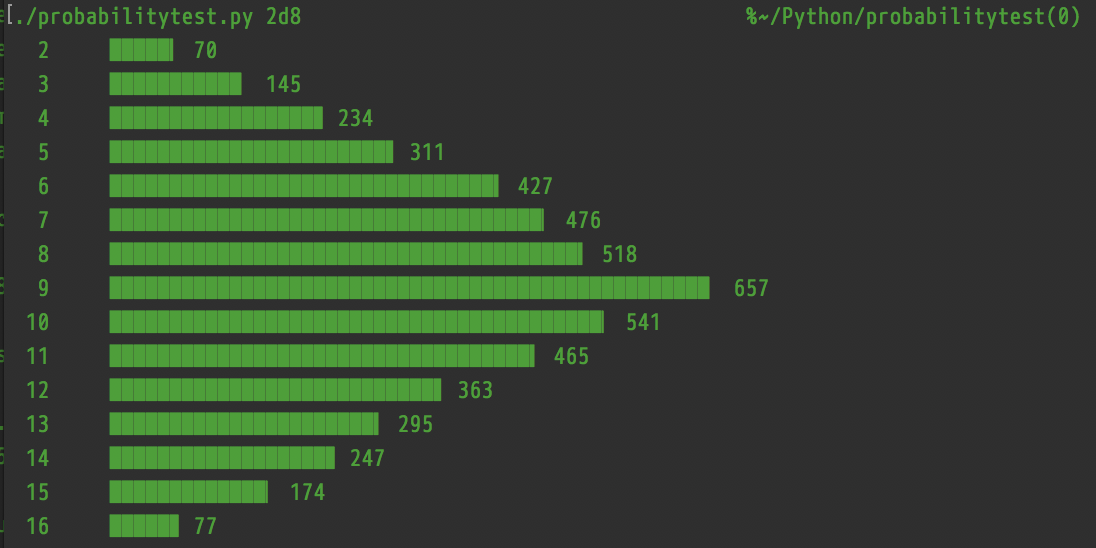

But I think lying to surveillance systems might have to be part of the short-term effort.

P.S.: I should say, I’m not 100% anti-automation. I think there are things that could be automated in ways that make us all better off. But we’re gonna have to be suspicious, and ask hard questions about whether any automation technology liberates us, or pushes us out of our own society—and, whenever possible, how we can ensure the former and not the latter.

P.P.S.: The day after I posted this, former Googler (fired for organizing) Laurence Berland wrote a thread, commenting on excerpts from a WaPo article, about a student-surveillance system for universities named “SpotterEDU”. One of the (many) problems with the system has been erroneous reports of lateness or absence—and the school taking the surveillance system’s side.

Of note, the mindset behind the development and deployment of the SpotterEDU system appears to be adversarial: assuming that students will flake out, lie about their attendance, make bogus excuses, etc. unless their movements are tracked at all times. That is to say, the system makes its (fallible, not-always-accurate) records of students’ locations without regard for the truth of the students’ accounts, because the system positions itself as the sole determiner of truth.