Why Mac programmers should learn PostScript

Saturday, April 7th, 2007I’ll follow this up with a tutorial called “PostScript for Cocoa programmers”, but today brings my list of reasons why you should care in the first place.

I’ll follow this up with a tutorial called “PostScript for Cocoa programmers”, but today brings my list of reasons why you should care in the first place.

You may remember Daniel Jalkut’s blog post about resolution independence, with its demonstration of the superiority in quality of vector graphics over raster graphics (using an EPS file that I created for him ☺).

The problem with using an EPS file, as I pointed out to him when I emailed him the file originally, is that EPS files are very slow on OS X. The current (Tiger) implementation of NSEPSImageRep uses Quartz’s CGPSConverter to convert the EPS data to PDF data, then instantiates an NSPDFImageRep (kept in a private ivar) that it has do all the real work.

That PostScript-to-PDF conversion is the bottleneck. You don’t want that multiple-second delay (yes, really) at runtime. Better to take it before runtime. At the time, I suggested that he use pstopdf to convert to a PDF file, then put the PDF file into his Xcode project to be copied into the app bundle.

But what if you decide later to change the PostScript file? You need to remember to run pstopdf again. EPS files are just PostScript source code, so why not treat them like any other source code file? Or, a better question: How?

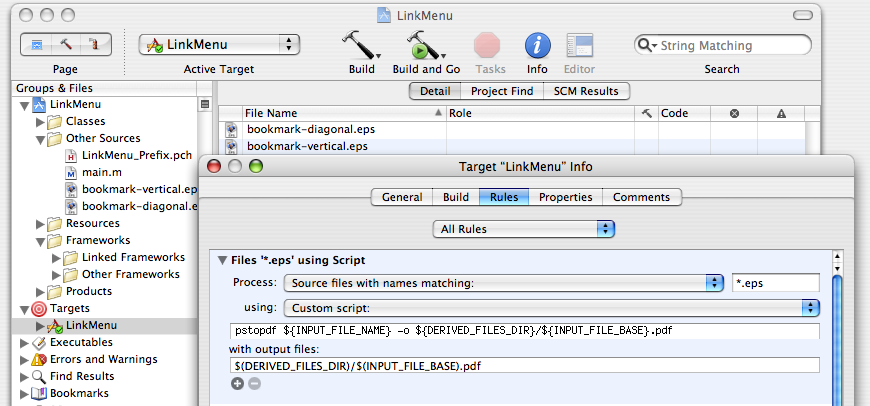

The answer is quite simple: Add a custom rule to your target in Xcode that runs pstopdf over EPS files. Then, you add the EPS file — not the PDF file — to the project, and Xcode will exhibit normal build-only-when-necessary behavior on the EPS file and copy the generated PDF file for you. And of course, you can have as many EPS files as you want — they’re source code files just like any others.

Sometimes, when I want to draw a graphic, I write it instead. I write it in PostScript, as an EPS file, and then convert to whatever destination format I want.

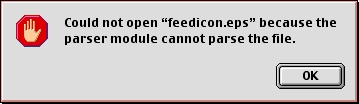

The problem with this plan is that I was never able to get Photoshop to import the EPS directly. I always got this error message:

Finally, today, I went looking for the solution. I used strings to see what the EPS Parser plug-in looks for. I found it in under a minute.

So, at minimum, this is what your EPS file must contain:

%!PS-Adobe-3.0 EPSF-3.0

%%BoundingBox: 0 0 width height

%%EndComments

The %%EndComments line is the one that I was missing. Make sure yours isn’t missing it too.

In case you want to know more, these special comments (% is the comment character in PostScript) are defined by the Document Structuring Conventions. EPS is an application of DSC.

Technorati tags: Photoshop, PostScript, EPS, EPSF.

I’ve recently been beating my head against PostScript’s gradient (“shading”) system. Plenty of documentation and examples are available for when you’re working in the DeviceGray color space, but when you’re in DeviceRGB, it gets hard. Part of this is due to the fact that the PostScript Language Reference Manual’s description of shadings and the functions that power them is overly abstract and decorated with too much math for my language-oriented mind.

So, here I’ll try and explain it more clearly, particularly by explaining functions in the context of shadings, rather than separately.

A shading in PostScript is represented by a dictionary. Valid keys in the shading dictionary are:

Functions aren’t as you expect them to be. Rather than a callable object (a procedure), a function is a dictionary. (This, BTW, is the architectural reason for Quartz’s CGFunction class, although CGFunction actually uses a C function callback — what would be a procedure in PostScript.) There are three types of function dictionaries; I’ll only deal with type 0, a sampled function (a “sample” is a step in the gradient). A sampled function contains, or fetches from a file, the samples it will return, in a “data source”.

[0 1]).DeviceGray, Range should be two numbers; in DeviceRGB, it should be six.You might expect that the samples should be given as an array. You would be wrong. Instead, PostScript wants pure binary data, either from a file or encoded as a string. So, for example, in RGB, every three characters (bytes) are one sample. I use a hexadecimal literal, or when I want to use an array, this procedure (which you may consider to be under the modified BSD license):

% array -> hexstr -> string

% Converts an array of integers to a string. [ 65 66 67 13 10 ] -> (ABC\r\n).

/hexstr {

4 dict begin

/elements exch def

/len elements length def

/str len string def/i 0 def

{

i len ge { exit } ifstr i

%The element of the array, as a hexadecimal string. If it exceeds 16#FF, this will fail with a rangecheck.

elements i get cvi

put/i i 1 add def

} loopstr

end

} def

And yes, I know that that procedure has nothing to do with hexadecimal. I was probably tired when I wrote it.

Note: If you use hexstr to create a shading dynamically from an array of samples, be aware that when you divide the length of the array by 1 (gray) or 3 (RGB) or 4 (CMYK) to get the proper value for Size, you must use cvi on the quotient, because div returns a real and makepattern demands an int.

Even better, it accepts line noise as input. From the manpage:

To put two pages on one sheet (of A4 paper), the pagespec to use is:

2:0L@.7(21cm,0)+1L@.7(21cm,14.85cm)To select all of the odd pages in reverse order, use:

2:-0To re-arrange pages for printing 2-up booklets, use

4:-3L@.7(21cm,0)+0L@.7(21cm,14.85cm)for the front sides, and

4:1L@.7(21cm,0)+-2L@.7(21cm,14.85cm)for the reverse sides.

pstops is part of psutils.